- MN ABE Connect

- Archive

- Close Reading and the CCR Standards Part II: Measuring Text Complexity

June 5, 2017

June 5, 2017

Close Reading and the CCR Standards Part II: Measuring Text Complexity

Kristine Kelly, Literacy & ELA CoordinatorAccording to Nancy Frey and Douglas Fisher, text-dependent questions are “questions that are answered through close reading of a complex and worthy text.” In the beginning of May, I wrote the article “Close Reading and the CCR Standards Part I: Some FAQs” and planned for this next article in the series to be about writing text dependent questions. However, as I tried to write, I kept thinking about text complexity, how it is related to close reading and how the information we get from delving deep into what makes a text complex often forms the basis for a set of effective text dependent questions and accompanying instructional scaffolds. Therefore… let’s talk text complexity before we go any further.

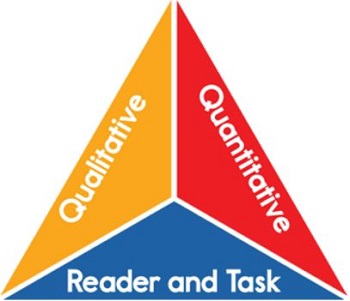

We cannot ask effective CCRS-aligned questions about text that isn’t complex with fully developed ideas, nor can we sustain our students through multiple reads during a close reading activity without using an appropriately complex text. But complex text isn’t simply reading text at a higher reading level or a poem or a textbook selection or a technical manual. We cannot simply “eyeball” text or rely on a grade level from a publisher to determine text complexity. Text complexity is made up of a combination of factors including quantitative measures, qualitative measures and reader and task considerations.

Quantitative Measure

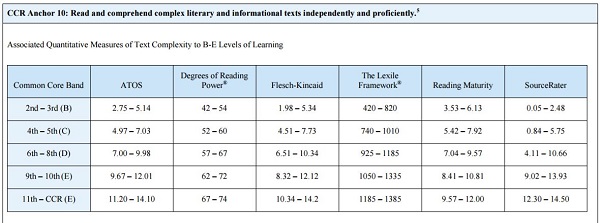

The quantitative measure of a text is determined by a computer. You may have heard of “Lexile” and “ATOS.” These are online tools that can provide a starting point for measuring text complexity. The formulas for calculating text complexity incorporate factors like sentence, paragraph and word length. But the formulas can change depending on the tool and the source and do not measure levels of meaning within a text. For the purposes of the CCRS, we recommend using Lexile or ATOS. When you get a text’s quantitative score, you can then compare it to the number bands included in CCRS Reading Anchor 10 to determine if the score falls into an appropriate level for the students you teach.

Quantitative tools give us a base measure of a text, but they do not measure other factors that can increase the complexity of a text for our learners. For example, I like to use the old Contemporary series Expressions and Viewpoints with my learners. The series was geared for reading levels of 4-7. My students’ levels begin at a TABE D 6.0, and most are preparing for the GED and post-secondary training. The quantitative measure from the publisher would indicate that this text wouldn’t be very complex for my students; however, the often sensitive themes, informal and idiomatic language, mixed text structures, background knowledge assumptions, use of literary devices, etc., can make the text quite complex for my students, especially depending on what I want them to DO with the text. For this reason, I must determine the qualitative complexity of the text.

Qualitative Measure

While we can notice some complexity factors fairly quickly when we glance through a text, some factors require a close reading of our own to measure effectively. In general, tools to measure qualitative complexity require a teacher’s professional judgment on the following text features:

- Text structure and layout

- Language clarity and conventions

- Knowledge demands

- Purpose

We have a useful rubric to help with qualitative analysis (information about where to find it is near the end of this article!). Note that the goal is not to use a rubric like this with every piece of text you want to use with your learners, only with text that you intend to use for an activity like a close reading experience. The rubric helps us to internalize what the CCRS means by text complexity and provides a way that teachers can talk to each other about common features. We must focus on measuring the text and NOT on our students during this part. Keep in mind the difference between complexity and difficulty: complexity lies with the text, while difficulty lies within each student’s ability to work with the complex text. Do not focus too much on a “right” answer when you use the rubric; view the tool as a way to identify potential areas of complexity to focus instruction.

We have a useful rubric to help with qualitative analysis (information about where to find it is near the end of this article!). Note that the goal is not to use a rubric like this with every piece of text you want to use with your learners, only with text that you intend to use for an activity like a close reading experience. The rubric helps us to internalize what the CCRS means by text complexity and provides a way that teachers can talk to each other about common features. We must focus on measuring the text and NOT on our students during this part. Keep in mind the difference between complexity and difficulty: complexity lies with the text, while difficulty lies within each student’s ability to work with the complex text. Do not focus too much on a “right” answer when you use the rubric; view the tool as a way to identify potential areas of complexity to focus instruction.

Going back to my Expressions and Viewpoints example, we recently read an essay that included a flashback, some informal and idiomatic Southern language, multiple ideas that required inferencing and an overall metaphor. These features increased the complexity of the text and were areas I knew I needed to focus on during instruction to help students access the deeper meanings of the text. I knew my students would be engaged with the content, but I wanted to make sure all the students had the opportunity to understand the text the way the writer intended.

Once we get at the heart of complexity within a text, we can then move onto the final step of measuring text complexity: reader and task consideration.

Reader and Task Consideration

When determining whether or not the text is appropriate for the students we currently work with, we must consider the following:

- Student motivation

- Prior experiences and knowledge

- Purpose of task

- Complexity of task

- Cognitive capabilities

- Content/theme concerns

- The student supports we need to put in place for instruction

Remember that we want the students to productively struggle with complexity. If at this point we determine that the only way we can use the text is to simplify words and sentences, spend a lot of time pre-teaching background knowledge and/or carry most of the struggle load ourselves for students, this text is not appropriate for a close reading, or the task we plan to give to students should change. The text may be appropriate for other instructional purposes or may not be appropriate at all for the current group of students. If students can productively struggle with the text to access meaning, we can build text-dependent questions and tasks that target specific features of the text’s complexity and create effective scaffolding to help students access these features.

For the Expressions and Viewpoints close reading my class did, I pre-taught only what was necessary to unlock initial understanding and provided sequenced text-dependent questions that targeted specific language, the content and purpose of the flashback and the overall metaphor of the story. Then, I created a task where students had to make inferences from parts of the text while also providing text evidence to support their inferences. Finally, I gave students a task to do some writing about advice the writer might give others based on what they could infer about the writer’s character and about the writer’s purpose. Though the quantitative reading level of the text falls between 4-7 GLE, the close reading and associated tasks proved to be complex and meaningful for my students.

Next Steps

This article was a fairly quick explanation of text complexity and how to determine it. See a much more detailed explanation of text complexity here. In addition, on the ATLAS website in the CCR Standards resource library, you will find a PowerPoint and materials from a regional workshop I did called “More Fun with Text Complexity! Really.” Some of the information provided there may be helpful. You will find the qualitative rubric I discussed above for determining text complexity available to download.

So far, we’ve taken a look at close reading and discussed both the concept of text complexity under the CCRS and how to determine complex features of text. Next time, we will build on these concepts and review how to create an effective, sequenced set of text-dependent questions for use in a close read of a text.

Newsletter Signup

Get MN ABE Connect—the official source for ABE events, activities, and resources!

Sign UpArticle Categories

- ABE Foundations/Staff Onboarding

- ACES/Transitions

- Adult Career Pathways

- Assessment

- CCR Standards

- Citizenship

- COVID-19

- Cultural Competency

- Digital Literacy/Northstar

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning/Education

- ELA

- Equity/Inclusion

- ESL

- HSE/Adult Diploma

- Listening

- Math/Numeracy

- Mental Health

- Minnesota ABE

- One-Room Schoolhouse/Multilevel

- Professional Development

- Program Management

- Reading

- Remote Instruction

- Science

- Social Studies

- Speaking/Conversation

- Support Services

- Teaching Strategies

- Technology

- Uncategorized

- Volunteers/Tutors

- Writing